Macro and micro

Micro: looking closely. Sometimes when I am out taking photographs of flowers and plants, I think of Georgia O’Keeffe and her famous close-up paintings of flowers.

Micro: looking closely. Sometimes when I am out taking photographs of flowers and plants, I think of Georgia O’Keeffe and her famous close-up paintings of flowers.

Flowers are among the many natural structures which amaze the viewer when we examine them closely. They may be seen as analogies, as, for example, many viewers interpret O’Keeffe’s flower paintings to be of female anatomy. In a broad sense, flowers are sexual: they exist (mainly) in order to get the egg and pollen together and make a seed which may fall later on fertile ground and become a new generation of the same plant. However, a simple depiction of the flower is not art (although I do love a good botanical drawing!). Art goes beyond portrayal of something that exists already. Art is a communication which aims at moving something deep within the viewer.

Art

Art

Visual art is a wordless communication which circumvents our verbal thoughts and touches directly on beauty, or horror. It works through some of the hardwired elements which give rise to rules of composition, and colour, and elements of a visual image which most viewers find pleasing and attractive. We may be moved to contentment by pleasured senses; or to an interpretation which inspires thought or challenges our social concepts. My concept of art excludes some photographs: on Twitter, for example, I see many images posted that portray some element of the world, but fail to reach deeper. There are trends today to enhance the ‘wow’ reaction to a photo. One example is increasing colour saturation of the muted colours (vibrancy). Some of the richly coloured sunset photos on Twitter are very attractive, in part because golden and warm colours also feel psychologically warm to us. However, for me, they belong with the brightly coloured tropical sea images – great colours, but what does the image say? This is in contrast to the rich colours of the night city shots by Peter Bialobrezski, whose enormous prints show details of life in crowded cities despite the night. Bialobrezski’s work conveys crowded cities, poverty, and trying to make ends meet, and also shows pastels of processed night shots which make the images themselves compelling.

Photography

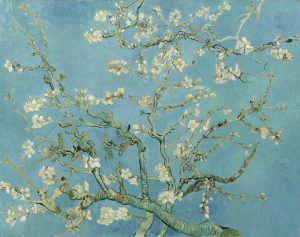

At the risk of sounding a bit overly simplistic, photography as a medium requires different viewpoint than painting. By this I mean, in photography, only some elements are in focus, while a painter may show all or much of the subject as in focus. A painting of a group of tree blossoms – such as van Gogh’s almond blossoms – is a delight to explore with the eye. Now imagine a similar photograph – without something to draw one’s eye, a photograph of many blossoms would not delight. If I were designing my composition of a photo of a flowering tree, I would try to highlight a blossom by having it closer to the viewer, or highlighted with light. Or I might include a blossom which has a salient and different colour, or design the composition to include a big patch of blue sky that adds a sense of spaciousness or escape, or a hand reaching up to touch some blossoms. A photograph, to be captivating, requires more of a story than a painting.

Macro

Macro

One way the story is told is by narrowing the viewer’s focus to a single feature or pattern, such as through macro photography. Macro photography relies on lenses which can focus closely and result in an image which is life size or larger. With a macro, the artist can present clearly something that is often overlooked. Plants make wonderful subjects for macro work, since they are intricately made and often have surprising colours or hairs when we examine them in micro. The gentle curves and soft colours can indeed remind us of the human body, and of associated feelings. Macro art should cause us to question something, or admire nature, after the first ‘wow’.

And, with spring here, it is the right time to explore up close, with camera in hand.